In advocacy work we raise concerns about risks that we hope will never actually happen.

But our concerns about risks of automated decisions were realised in January 2024 when we learnt about an error with the Targeted Compliance Framework (TCF). This glitch that was reported in a Guardian blog post1 wrongly applied 1625 payment penalties to 1165* individuals between 2018 and 2023.

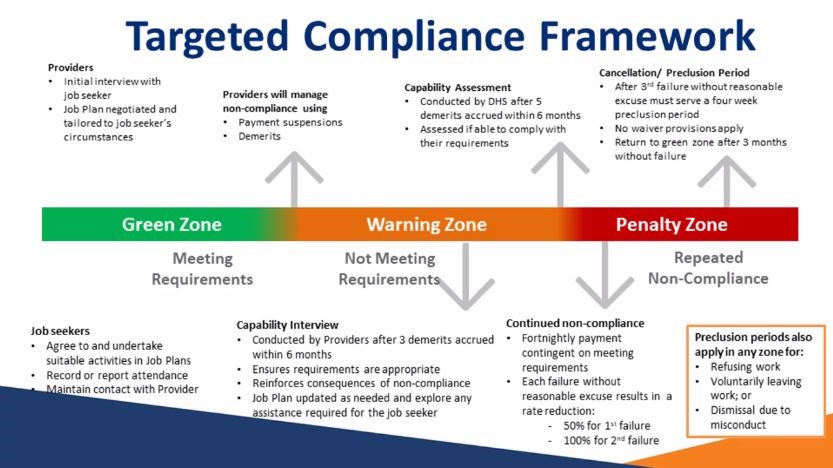

The glitch was caused by incorrect coding of a rule that resets people in the TCF Penalty Zone to the Green Zone after 91 days of ‘good behaviour’ (see below for more info on the TCF and glitch). The glitch incorrectly calculated the number of days a person was required to remain in the TCF ‘penalty zone’ before being reset to the green zone for ‘good behaviour’.

To examine the impact of the glitch we have tallied the available data on payment penalties2 for all relevant periods3. There were fewer payment penalties in 2020 and 2021 because of COVID mutual obligations pauses and the incidence of penalties did not escalate significantly again until January 2023.

Table 1 shows that 2-7% of the overall number of payment penalties were glitch penalties. It shows glitch-related payment penalties as percentage of overall penalties for the relevant period.

Table 1 – Glitch penalties as percentage of all financial penalties in TCF 2018-2023

| FY Jul-Jun | 1st Penalty | 2nd Penalty | 3rd Penalty | Total |

| 2018-19 | 8,291 | 5,050 | 2,106 | 15,447 |

| 2019-20 | 8,442 | 5,081 | 2,180 | 15,703 |

| 2020-21 | 524 | 261 | 78 | 863 |

| 2021-2022 | 7676 | 4669 | 2172 | 14517 |

| 2022-2023 | 3480 | 1620 | 500 | 5,600 |

| Total all years | 28,413 | 16,681 | 7,036 | 52,130 |

| Glitch affected | 427 | 714 | 474 | 1625 |

| % of all | 2% | 4% | 7% | 3% |

Source: Author calculation based in DEWR submission 254.2 and published TCF data

While it is true that the glitch applied to a small percentage of payment penalties overall, the impact of the glitch for the 1165 people impacted was likely to have been significant. This is especially the case for people affected by the 3rd penalty, whose payments were cancelled and who had to re-apply for payments, meaning they were without income support for at least 4 weeks.

It is also the case that First Nations people, people experiencing homelessness and ex-offenders are over-represented in payment penalty data, and are less like to request a review of a decision because of their relative disempowerment. This may explain in part why the glitch went undetected for almost 5 years.

EJA prepared questions for DEWR to elicit more information about how the glitch including:

- what the coding error was and how it calculated payment penalties wrongly

- the quality of assurance processes relating to commissioning of IT systems for the TCF and its adherence to social security law

- why no complaints about the payment penalties appeared to have been registered or used to investigate potential for errors in the TCF system design,

- why complaints about financial penalties that may have been lodged with Services Australia had not been reported to DEWR , and

- why complaints had not led to review of the IT system settings.

- whether there had been checks on the welfare of the people who had been affected

- how the remediation of the issue was being managed,

- and whether there were offers of compensation to persons who had wrongfully had their payments cut off for period of 1 or 2 weeks or cancelled altogether.

DEWR informed EJA that the glitch remediation process was being handled by Services Australia who are contacting people to offer them backpay and that the glitch has also contributed to improvements in internal processes.

Learning from this glitch

The TCF glitch provides lessons across three areas of social security: IT design, accurate decision making and access to review, and use of complaints processes to identify system problems.

IT design: It appears that the glitch went undetected for so long because there were no processes for checking the IT system was making decisions in accordance with social security law. The glitch was only identified as part of DEWR’s program assurance activities rather than part of the testing or ongoing quality assurance of the IT system itself.

Accurate decisions making and access to review: There were inadequate checks in the process of administering payment penalties to ensure that all the criteria for the penalty were met. There also appears to have been inadequate explanations provided to the people affected that would have enabled them to understand the complex rules relating to the penalty. It is also concerning that at the time of writing4 there is an automated process that enables people to accept penalties without a full explanation of the reasons for it, and this has further limited that ability to understand whether the penalty was justified.

Complaints processes: No complaints about the glitch were identified by either DEWR and Services Australia probably because people were unaware of the rule relating to the 91 day period. This suggests a need to more closely examine complaints about payment penalties to identify whether the rules relating to the administration of the decision have been applied appropriately.

The lessons from the glitch issue suggest room for improvement across all three of these areas. While DEWR has already committed to a review of complaints processes5 and a change to the IT system so that people cannot automatically accept a penalty, it is EJA’s view that these initiatives should also be accompanied by processes to:

- Ensure that all automated processes are subject to user testing that includes simulation of the scenarios they have been designed to automate

- Provide access to Authorised Review Officers in DEWR to ensure that ‘complaints’ about mutual obligations are reviewed appropriately, including with an understanding of how the IT system has made a decision

- Identify systemic issues through regular review of complaints and compliance penalties.

- Improve employment services participants’ access to review of decisions and ensure they are provided with full written reasons for any payment penalty that includes information about the rules.

- Publish lists of complaints that lead to reviews, and the decisions that are made, and.

- Publish data on the incidence payment penalties and cancellations by cohort to identify over-representation of vulnerable people.

In order to build trust about the use of automated decision-making processes in employment services DEWR should also:

- Undertake a complete audit of all automated processes to ensure they are lawful and that complex business rules work as intended.

- Be transparent about IT issues, who they affect and how they are being resolved

- Provide a public register of IT downtime and issues,

- Publish an account of internal processes being undertaken to prevent similar issues occurring.

The TCF glitch issue underscores the need for decisions relating to social security payments to be administered by human decision makers, who can check the material facts of the case whenever a person disputes a decision. Further, the rules of the TCF are very complicated, while simultaneously lacking the flexibility to ensure that people who are experiencing persona crisis are not subject to financial penalties. The TCF glitch has shown how there is a need to move to a far less punitive approach to compliance.

Background on the TCF and the glitch

The legislative basis for the 91-day penalty zone rule, and the application of financial penalties for wilful non-compliance are set out in a determination6. This determination provides for the administrative process of the TCF.

The TCF uses automated payment suspensions and demerit points that accrue towards financial penalties called payment penalties. Once a person has accumulated 3 demerit points they have a capability interview with a provider, and on the 5th demerit point they have a capability assessment with Services Australia. The capability interview and assessment involve a review of personal circumstances and determines if their mutual obligations as set out in the job plan requirements are appropriate. If a person is found capable of meeting the job plan requirement, they enter the Penalty zone, where each subsequent mutual obligation failure results in a payment penalty.

The payment penalty is administered by Services Australia’s Participation Solutions Team (PST). The investigation of the penalty draws on information entered into the IT system about a mutual obligation failure – these are most often because people were not recorded as having attended an appointment or not having met a points target under the Points-based activation system. The PST contacts the person to discuss the current mutual obligation failure and then apply the penalty if there is no reasonable excuse. A person can also access the financial penalty by accepting a system prompt (this latter functionality will be phased out in 2024). The PST assessment of the mutual obligation failure is based on whether there is a reasonable excuse that meets the definition in the Operational Blueprint and as is set out in in legislation.

A person remains in the penalty zone for 91–days and if there is no further mutual obligation failure they are clean-slated to the green zone. If there is a mutual obligation failure the person loses 1 week payment for the first, 2 week’s payment for the second, and for the third failure they are cancelled of income support for 4 weeks, and must reapply, After each penalty the person remains in the penalty zone for an additional 91 days and when they reapply for payment after the third penalty, they return to the penalty zone.

The TCF glitch meant that if a person was cleared of a mutual obligation failure during a 91 day stretch in the penalty zone the clock was reset to add another 91 days. This means they were erroneously required to serve another 91 days in the penalty zone, rather than having the days they had already served in the penalty zone subtracted from the 91 days. This effectively worked as time-added on to the 91 day penalty zone period.

(Source: Targeted Compliance Framework chapter of the Workforce Australia guidelines7)

*This figure was revised to 1326